A Silence in September

by Richard G. Johnstone Jr., Editor

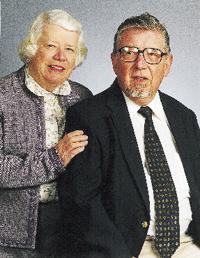

L. John Trott Jr.,

Naturalist and Teacher

1927-2000

In the increasingly

urban Virginia of the early 21st century, he taught our 300,000-plus readers about wild

things, such as the virgin forest that blanketed the eastern U.S. when Europeans first set

foot here 400 years ago, and which is now confined to a few scattered fragments. And, of

course, most of all he taught us — with passion and purpose, filled with lively

anecdotes and historical tidbits — about the birds that frequent the Old Dominion.

But like the birds he loved and captured on film and through words, his sweet song was all

too brief, being stilled by a heart attack on September 6. He leaves behind his devoted

wife of 39 years, Lenore or "Lee" as he called her affectionately in his

columns, plus legions of colleagues, friends and regular readers of this magazine.

In the increasingly

urban Virginia of the early 21st century, he taught our 300,000-plus readers about wild

things, such as the virgin forest that blanketed the eastern U.S. when Europeans first set

foot here 400 years ago, and which is now confined to a few scattered fragments. And, of

course, most of all he taught us — with passion and purpose, filled with lively

anecdotes and historical tidbits — about the birds that frequent the Old Dominion.

But like the birds he loved and captured on film and through words, his sweet song was all

too brief, being stilled by a heart attack on September 6. He leaves behind his devoted

wife of 39 years, Lenore or "Lee" as he called her affectionately in his

columns, plus legions of colleagues, friends and regular readers of this magazine.

John Trott began

writing for us in early 1998, and his first column in the March/April issue that year was

titled, "The Cardinal: A Good Omen." That particular column focusing on

Virginia’s state bird was certainly a good omen for us, as the 27 columns he would

ultimately write for us —all featuring the superb photos that would become his

signature — became among the most popular features in Cooperative Living.

John Trott began

writing for us in early 1998, and his first column in the March/April issue that year was

titled, "The Cardinal: A Good Omen." That particular column focusing on

Virginia’s state bird was certainly a good omen for us, as the 27 columns he would

ultimately write for us —all featuring the superb photos that would become his

signature — became among the most popular features in Cooperative Living.

I’d like to say I knew John Trott well, since I feel that I did through the

friendly, conversational style of his writing, the exquisite beauty of his bird

photographs, and the occasional phone call I enjoyed with him. And just as cooks swap

recipes and fishermen swap lies, he and I would "swap" favorite books on nature.

I recommended Hal Borland’s This Hill, This Valley, and Henry Beston’s Northern

Farm.

He suggested Edwin Way Teale’s autobiographical A Naturalist Buys an Old Farm. In

it, Teale wrote poetically and in John Trott-like fashion about the flight of the woodcock

at dusk on March nights: "There is always something particularly moving about the

ecstasy of this dull-appearing brown and dumpy bird, this feeder on earthworms, this

boggy-ground dweller, as it mounts up and up into the sky and then plunges with its wild

gyrations back to earth again. It seems a spirit unfettered for a time, transcending its

ordinary days, attaining a superlative moment. There is something symbolic about its

flight." John Trott’s writing was much like that, deceptively simple,

"attaining a superlative moment" through his loving descriptions of birds and

his richly colorful photographs of them.

Another of John

Trott’s favorite writers, Aldo Leopold, wrote the landmark conservation classic, A

Sand County Almanac, in 1949, and at the end of a long chapter on the natural history of

the U.S., Leopold wrote, "These things I ponder as the kettle sings, and the good oak

burns to red coals on white ashes. Those ashes, come spring, I will return to the orchard

at the foot of the sand hill. They will come back to me again, perhaps as red apples or

perhaps as a spirit of enterprise in some fat October squirrel who, for reasons unknown to

himself, is bent on planting acorns."

Another of John

Trott’s favorite writers, Aldo Leopold, wrote the landmark conservation classic, A

Sand County Almanac, in 1949, and at the end of a long chapter on the natural history of

the U.S., Leopold wrote, "These things I ponder as the kettle sings, and the good oak

burns to red coals on white ashes. Those ashes, come spring, I will return to the orchard

at the foot of the sand hill. They will come back to me again, perhaps as red apples or

perhaps as a spirit of enterprise in some fat October squirrel who, for reasons unknown to

himself, is bent on planting acorns."

John Trott spent over 40 of his 73 years as a teacher of botany and ornithology, in

both public and private schools. He also taught through his nature column in this

magazine, and through a separate column he wrote for several Virginia weekly newspapers

near his home in Rappahannock County’s Flint Hill.

Like the oak ashes described by Leopold, John Trott’s words and images will

continue to come back to me, and undoubtedly to thousands of his devoted readers.

We’ll remember John Trott as we watch and admire the juncos and sparrows and evening

grosbeaks and purple finches and chickadees and goldfinches and blue jays and woodpeckers

that he studied in the great classroom of the outdoors, and taught us about in the

"textbook" of a magazine column.