The

Beauty Beneath Your Feet

by

Deborah R. Huso, Contributing Writer

|

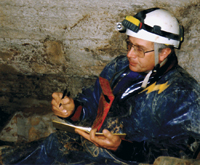

Bath

County resident Matt Campagna navigates a narrow passage in one of

Virginia's multitudinous non-commercial caves.

|

While Virginia�s Shenandoah Valley is

renowned for its scenic beauty, one of its most

stunning features is actually under the ground.

Living in Highland County, I find it

difficult not to be intrigued by what�s under the ground. Our landscape here, just west of the Shenandoah

Valley, is one where sinkholes attest to a world existing beneath

us � a world full of dark chambers, flowing water, and formations of

flowstone never yet seen by man. Once, behind my house near Bolar Springs, I

came across a hole in the ground, its mouth marked by a ring of rock, a

crooked tree just above it with an old rope attached, a rope that extended

down into the hole. I peered into the blackness wondering who had been brave

enough to crawl into that dark netherworld. Many times I returned to the

spot, trying to imagine what might be down there. A single dark chamber?

Tunnels curving beneath the mountain for miles? Formations that would

glisten against the illumination of a flashlight?

Venturing into a wild cave alone seemed

too much for me. But that�s how many of Virginia�s show caves were

discovered � once a boy, or a dog, or an adventurous farmer found an

entrance into the earth, then someone went in and discovered a vast, strange

world dripping with the life of slowly growing stalactites. That�s how

Virginia�s most popular cavern at Luray came to be � discovered by a

local tinsmith and his friends in 1878. It has been a show cavern almost

ever since, even drawing the attention of North Pole explorer Jerome J.

Collins and the Smithsonian Institution.

How the Valley�s Caves

Began

Given the ease with which we can visit a

place like Luray Caverns today, it�s difficult to imagine just how ancient

the caves of the Shenandoah Valley are. They�ve been formed over

millennia, starting with the movement and breaking-up of continents 600

million years ago. Caverns like those in Luray formed when a prehistoric sea

drained out of a massive basin running from Newfoundland to Alabama. With

the uplift of the Appalachian Mountain range and the drainage of vast areas

of water, caverns began to form and inside them a multitude of otherworldly

formations.

When one considers that at Luray

Caverns, deposits of crystallized calcite, which form stalactites and

stalagmites, grow at a rate of one cubic inch every 120 years or so, the

insignificance of a human lifespan becomes clear. Perhaps that�s part of

what draws half-a-million visitors a year to this Shenandoah Valley

attraction.

Luray Caverns

|

"Frozen

Fountain" at Luray Caverns. All formations in the caverns are

calcite, a crystalline form of linestone, the result of linestone

dissolved in water, then re-depositied in the hollowed-out

underground chambers as stalactites and stalagmites. |

Luray Caverns� history is almost as

interesting as its formations. In 1901, 23 years after the cavern�s

discovery, Col. T.C. Northcott leased the property and used the caverns to

generate air conditioning by putting a five-foot-diameter shaft with an

electric fan into one of the cave�s chambers to push cool air into the

sanitarium he built over the caverns. Northcott called it the first

air-conditioned home in the U.S., as the fresh and clean cavern air

maintained a temperature of about 70˚F throughout the building.

Today visitors to Luray Caverns can

still enjoy natural air conditioning. The caverns maintain a temperature of

about 54˚F year-round. A designated National Landmark, the caverns are

the largest in the East and feature a variety of aptly named chambers,

including Giant�s Hall, which is dominated by 10-story- high gold columns.

Luray is perhaps best known for its stalacpipe organ, a real organ that

creates sound through the use of stalactites as organ pipes. Over

three-and-a-half acres of stalactites are fitted with rubber mallets wired

to the organ to bellow out eerily beautiful music. (540) 743-6551, www.luraycaverns.com.

Shenandoah Caverns

Shenandoah Caverns, near Mt. Jackson,

was discovered in 1884, during construction of the Southern Railway when

local blasting activity exposed vapor rising from a crevice in the earth,

drawing some boys to explore the crevice. What they found, with only the

help of some candles, was a vast underground room with dripping, glistening

formations. Today the caverns is known for its 17 underground rooms,

accessible via elevator. The site has been open to the public since 1922.

Among the unique features of Shenandoah

Caverns is Rainbow Lake, where a pool is surrounded by multi-colored

dripstone, and Diamond Cascade, a massive pointed calcite crystal formation

all in white. Visitors also enjoy Shenandoah�s bacon formations, which

literally look like massive strips of pink bacon stretched out against the

walls. Visitors should also be sure to look for Shenandoah Caverns� pixie,

the cavern mascot developed in the 1960s, who can still be found hiding at

various places among the underground formations. (540) 477-3115, www.shenandoahcaverns.com.

Grand Caverns

|

The

"Ski Slope" at Grand Caverns. |

Located near Natural Chimneys, Grand

Caverns is the nation�s oldest show cave, having offered public access

since 1806. Despite its name, it�s not the largest in the Valley, but does

have the most well-documented history. During the Civil War, both

Confederate and Union soldiers visited the caverns and wrote their names on

the walls. 230 of those signatures have been verified, and some are visible

to visitors on the cavern tour. Legend says that General Stonewall Jackson

refused to tour the caverns, explaining, �I fear I shall be underground

soon enough, and I have no desire to speed the process.� Today visitors to

the caverns can explore Cathedral Hall, a vast underground room 280 feet

long and more than 70 feet high. Drapery-like flowstone garnishes the walls,

while thick and massive columns stretch from floor to ceiling. Other

signature formations of Grand Caverns include the Bridal Veil, Stonewall

Jackson�s Horse, and Dante�s Inferno. (888) 430-2283, www.uvrpa.org/grandcaverns.htm.

a

one-of-a-kind attraction

Luray Caverns� Great Stalacpipe Organ

is the world�s largest musical instrument. This one-of-a-kind wonder was

conceived by Mr. Leland W. Sprinkle of Springfield, a mathematician and

electronics scientist at the Pentagon. After visiting the caverns with his

son and experiencing the sounds of a stalactite being tapped, Mr. Sprinkle

submitted a complex plan for the instrument. It took 36 years of research,

design and experimentation to build. Three years alone were spent searching

the caverns to select and carefully sand stalactites to precisely match the

musical scale; only two stalactites were found to be in tune naturally. The

four-keyboard console was constructed by the Klann Organ Supply Company of

Waynesboro to meet the peculiar needs of a subterranean installation. The

organ is connected to various stalactites by over five miles of wiring.

Today, the organ is played by an automated system, but can also be played

manually from the console, as Leland Sprinkle did for many years.

A

Glossary of Formations

More

Shenandoah Valley Caverns To Visit

Natural

Bridge Caverns

Natural

Bridge

(800)

533-1410

www.naturalbridgeva.com

Endless

Caverns

New

Market

(800)

544-CAVE (2283)

www.endlesscaverns.com

Skyline

Caverns

Front

Royal

(800)

296-4545

(540)

635-4545

www.skylinecaverns.com

Crystal

Caverns

Strasburg

(540)

465-5884

www.waysideofva.com/crystalcaverns

Virginia�s Wild

Cavers: Why They Love the Underground

|

Seasoned

spelunker Rick Lambert. |

Many of us have experienced a trip into

the earth via one of Virginia�s many commercial caves, our path happily

brightened by hundreds of strategically placed lights and paved walkways

leading us into underground rooms of brightly colored formations, clear

spring pools, and artifacts of man�s earliest trips into darkness. But

this isn�t all there is to exploring Virginia�s underground world. The

mountains west of the Blue Ridge, rich with limestone eroded into tunnels

and rooms by centuries of seeping groundwater, are home to caves by the

hundreds, most of them privately held and not accessible to the general

public.

But for those among us who are serious

spelunkers, who have no fear of mud, water, slime, and darkness, the wild

caves of Virginia offer endless opportunities for discovery, scientific

research, and a view into a world untouched by time.

Serious Spelunker: Phil

Lucas

It is an understatement to say that Phil

Lucas of Burnsville takes caving seriously. He has been president of the

Virginia Speleo�logical

Survey (VSS) since 1974, and now retired, he devotes himself full-time to

the exploration, mapping, and surveying of Virginia�s caves. He says there

are 4,378 known caves in the Commonwealth, most occurring in 26

limestone-heavy counties west of the Blue Ridge. One of those counties,

Highland, is where Lucas has made his home for the last six years,

appropriately enough on a 160-acre farm that holds entrances to six caves.

Lucas says he first became interested in

caves as a young boy growing up north of Harrisonburg, where, by age 7, he

had already spent some time in commercial caves and had traipsed along with

his brother and a friend who discovered a cave near Lucas� boyhood home.

�I was enthralled,� he says of his first trip into that wild cave that

he later revisited as an adult. �As a kid, I stuck a bunch of candles in

my hip pocket and hopped on my bicycle to go caving.�

Lucas� spelunking is a little more

sophisticated these days. �Most people think of caving as caving for sport

or as a hobby,� he notes. �But caves are a finite natural resource

deserving of protection.� Lucas says the mission of the VSS isn�t to go

tramping around the state�s wild caves but �to collect, protect, and

disseminate information on caves.�

The basement of Lucas� home is VSS

database central. Here he has some 1,900 maps of Virginia caves, almost all

of them surveyed by volunteers like himself. He also keeps on file

information on individual cave lengths, formations, features, artifacts, and

organisms. But all of this data isn�t publicly accessible. VSS doesn�t

advocate sending the general public into the state�s fragile cave systems,

and most of the data is col�lected

for the purpose of scientific study and to provide assistance to government

agencies like the Vir�ginia

Department of Conser�vation

and Recre�ation

and the Division of Mines and Minerals.

In his lifetime of spelunking, Lucas

says he has surveyed or helped survey hundreds of wild caves, noting

geological formations, hydrological patterns, as well as archaeological and

historic features. �It�s a very slow, tedious process,� he notes. But

it�s also a process rich with discovery. �A cave is like a time

capsule,� he explains. �Generally, it doesn�t have weather, so

everything inside is so well-preserved.�

Preserving Virginia�s

Wild Caves

Gregg Clemmer, president of the Butler

Cave Conservation Society, completely understands the timelessness of this

underground world. It�s not unusual to find fossils in caves. �You have

to get into the mindset,� Clemmer says, �that the stuff you�re seeing

may go back to the age of dinosaurs.� Clemmer had an up-close and personal

experience with the ages when he found footprints of a fisher, a fox-like

marten, about 400 feet from the entrance of a cave he was surveying.

�Fishers haven�t been seen in Virginia since 1810,� he explains. So he

knew he had discovered footprints that were at least 200 years old. After

further investigation, Clemmer discovered that flowstone in the cave had

covered some of the fisher�s tracks, which appeared to stop abruptly at a

steep drop-off. �The flowstone came after the fisher,� he explains,

�and that flowstone was thousands of years old, meaning those

well-preserved footprints were also thousands of years old.�

Remarkable discoveries like this inspire

cavers like Clemmer and Lucas to preserve this fragile underground

environment. That�s why a core group of interested cavers joined forces in

1968 to form the Butler Cave Con�servation

Society (BCCS), designed to help protect Butler Cave, which was discovered

in 1958 by CIA cartographer Ike Nicholson and has 16 miles of mapped

passages. At the time, Butler Cave was Virginia�s largest, but has since

been eclipsed by three others. In 1975, the BCCS raised enough money to buy

Butler Cave and 65 surrounding acres. �The purpose,� says Clemmer,

�was to control access to the cave to preserve it. And it�s worked.

After nearly 50 years, the cave is a good reflection of good cave-management

policy.�

Today the BCCS has about 45 members, all

of whom have a key to the cave entrance. This doesn�t mean the cave is off

limits to non-members, but BCCS members must accompany any visitors into the

cave.

While it�s illegal in Virginia to take

or touch any biological or archaeological artifacts in caves, not everyone

is respectful of this law. Clemmer notes that caves feature �very delicate

environments� that should be treated with care. �Plus, caving is

arduous,� he says. �You have to be in good shape to do it.�

If You�re

Serious About Caving, Be Prepared

|

Seasoned

spelunker Phil Lucas has logged countless hours in the

Commonwealth's wild caves. |

Rick Lambert, owner of Highland Adven�tures in Monterey, knows

all about the rigors of spelunking. He�s been leading wild cave tours in

western Virginia and West Virginia since 1991. He, too, cannot emphasize

enough the need to be physically fit to enjoy caving. �You need to be able

to pull your own weight up over a door,� he says. �If you�re over 200

pounds, you probably shouldn�t do it.�

And caving is a dirty sport. Cavers can

expect to be covered from head to toe in mud both inside and outside of

their clothes, and swimming may be involved as well as crawling through

incredibly tight places. �Most first-time cavers come in jeans and a

cotton T-shirt,� says Lambert, �but in caving, we say �cotton

kills.�� That�s because cotton holds moisture close to the body.

Lambert says the ideal attire is long polypropylene underwear and a nylon

outer coating to keep warm and dry. With the cool temperatures inside a

cave, someone who gets wet and cold can find himself suffering from

hypothermia very quickly.

Lambert also says one should never go

caving alone. �The smallest group should have at least four,� he notes.

That way if someone is injured, there�s someone to stay with the injured

person and two people to go for help. Lambert rarely takes fewer than 10

people at a time into caves and usually works with organized groups like

college classes or corporate groups. His minimum charge for a half-day

caving trip is $400, and that�s for a group up to 10.

Lambert says anyone interested in trying

out caving should be prepared ahead of time, not just physically and

equipment-wise, but also mentally. �Make sure you know what kind of cave

you�re going to,� he says. �You could run into a pit where you have to

rappel or a place where you have to swim.�

What Can You See?

Wild caving isn�t like touring a

commercial cave where everything is well-lit. A wild caver lights his way

with a head lamp and/or handheld light source. And what one sees underground

can vary from one cave to another. Some are rich with colorful formations;

others may be mostly mud and rock. And there�s a lot more to caves than

the well-known stalactites and stalagmites so familiar in places like Luray

Caverns. One of the caves on Lucas� property, for instance, is rich with

its namesake formation � helictites. These are curious curling calcite

formations.

One could also come across human

artifacts. Lucas says some Indians placed their dead in caves along with

beads and other artifacts that remain well-preserved because of the

consistent cool cave climate. Some caves were mined for saltpeter,

particularly during the Civil War, and might have remnant artifacts of those

operations.

One might also see bats, amphibians, crustaceans,

flat worms, insects, and beetles. Creatures who live in caves year-round and

don�t just use them for shelter and hibernation (as bats do) are called

troglodytes. �The food supply in caves is very limited,� says Lucas.

�It�s only what gets washed in there, so organisms in caves are very

small.� Lucas says most of the new species discovered in recent years have

been discovered underground.

That�s what draws Lucas to caving �

the fact that it�s man�s last frontier into the unknown. �When you

step into a black void, you don�t know what to expect,� he says.

�It�s really special.�

Wild

Caving Safely and Respectfully