|

Through Hell's Gates

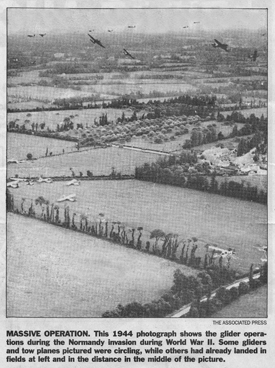

WWII Glider Pilot Recounts Journey

Story and Photos by Bill Sherrod,

Editor

|

Robert C. "Cal" Moore, Jr.

|

Some of the boys said it was like flying into hell.

Me, I was too busy trying to control the aircraft to think much about

what was going on outside.�

The aircraft was a CG-4A Waco glider. The place was

Normandy, France. The date was June 4, 1944. The man piloting that glider

into harm�s way was Robert C. �Cal� Moore, Jr., a 25-year-old Virginian with

a love of flying that led him into the glider service, among the most

hazardous duties in World War II.

�I was one of the lucky ones. I got the glider down,

without crashing,� Moore says with his trademark smile. That smile and his

easygoing manner have defined Cal Moore throughout a life rich in

experience.

Today Moore, at age 92, is still going strong. Retired

since the early 1980s from the Sales and Engineering Department of General

Motors, Moore lives in the same Appomattox County home he built right after

World War II. He also maintains a river cottage at Deltaville, where he

indulges one of his favorite pastimes, fishing. He regularly gives talks

about his war experiences to groups ranging from college ROTC classes to

community civic organizations.

Amherst County Native, Reared in Appomattox

County

Moore was born in the tiny community of Stapleton, in

Amherst County, on July 8, 1918. �Back then, there was a one-room

schoolhouse in Stapleton. The community�s not there anymore,� Moore notes.

At age 5, his family moved to Appomattox County, at his

mother�s urging, so young Cal could get an education. When he was about 10,

Moore�s dad got Cal a ride on a biplane that had flown into Appomattox. From

that point forward, he was hooked on airplanes. By the time he graduated

from Appomattox High School in 1936, he�d developed an equally intense

interest in cars, one he would indulge as a career with General Motors Corp.

after he left the service.

In his teens, Moore and a friend rebuilt a Nicholas

Beazley NB-3 airplane from the parts of a crashed plane, and Moore amassed

more than 200 hours of flight and flight training.

Moore got his pilot�s license at age 16 and, at age 18,

he was the youngest barnstormer pilot in Virginia, flying an old OX-5

eight-cylinder-engine Travel Air 2000 biplane, �A beautiful airplane,�

according to Moore.

Moore entered the Army in 1941, three days before Pearl

Harbor.

|

�I�d already (before Pearl Harbor) made application for

flying cadets training,� Moore recalls. �I�d been in three days when the

Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor.� For a while after that fateful day, life in

the Army was chaotic.

�When things finally settled down and I got squared away,

I got into the flight program. We had all kinds of training, all around the

United States � flight training, airborne training, and behind-the-lines

combat training, crawling underneath live ammunition.�

Moore�s military flight training included advanced

instruction in powered flight, as well as glider and sailplane training.

During his time in Europe with the Army Air Corps, he flew C-47 cargo planes

and other powered aircraft, in addition to the gliders.

�They held us back here in the States until six weeks

before the (D-Day) invasion,� Moore says. �The gliders had already been

transported to England, but the Germans were sending buzz bombs

(jet-powered, unguided missiles) into England, and the air force didn�t want

to lose pilots to those buzz bombs.�

Three Successful Glider Combat Missions

Moore�s D-Day flight into Normandy was the first of three

harrowing combat sorties he would fly before the end of the war. On the

Normandy mission, he was carrying an ambulance jeep and support troops to a

landing zone 13 miles inland from Omaha Beach.

�I was stationed at a little base in Southern England,

south of Bristol. We left in the early morning. It was a relatively smooth

flight, until right before touchdown.

�The Germans had dug square holes in the field I was

headed into,� Moore recalls. �They�d planted grass in the bottoms of the

holes, so you couldn�t see them from the air � it all looked nice and green.

�The Germans had also trimmed the cottonwood trees down

so, from above, they looked like shrubs. But when we came in, they were

trees, so we had to get over them and then try to land in these fields full

of holes.�

Moments before setting the unpowered glider down, Moore

saw the holes � obstacles that would have wrecked the glider and killed or

injured him and the troops he was bringing into France. �I still had enough

aileron control to kick it all the way out past the holes and set the glider

down nice and easy,� he notes.

�My job was to get the glider

down safely, and stay with it until the equipment and troops were unloaded,

then to get back to the beach any way I could.�

Moore did his job, and became one of the lucky glider

pilots who returned to his base in England unscathed. According to the

National WWII Glider Pilots Association, at the height of the glider

program, American combat glider pilots numbered less than 6,000. Their

casualty rate of 987 glider pilots � 16.4 percent of their total number, and

roughly 20 percent of those who flew in each combat mission � was one of the

highest of any combat specialty in World War II.

Market Garden

|

Moore�s second mission, on Sept. 17, 1944, was a flight

into Holland as part of Operation Market Garden. His cargo was an anti-tank

gun, ammunition and three support troops.

�This was a hard trip,� Moore recalls. �About 80 miles of

it was over enemy territory, and I had no co-pilot.� So many glider pilots

had been killed at Normandy that on subsequent trips, most of the aircraft

carried only one pilot.

�We used canals for navigation on the flight in,� Moore

adds. �There were these barges in the canals, and all of a sudden we

realized there were German antiaircraft guns on the barges, and they started

shooting at us.�

Moore says as shells burst near the glider and, as

shrapnel ripped through the glider�s fabric covering and dinged its

metal-tubing skeleton, a ringing sound would resonate up and down the length

of the fuselage. Moore remembers that when the glider would take a hit,

�That flak would play a tune on the steel tubing!�

It wasn�t the kind of music anyone on the Waco wanted to

hear, though, and it ended � suddenly, abruptly and violently � moments

later.

The RAF � Britain�s Royal Air Force � was flying high

cover, and out of the blue � literally � the Spitfires thundered in, guns

blazing. �I looked down and those gun barges had disappeared in a cloud of

smoke, and there was no more flak.�

Moore was leading the left echelon of this flight, and

guided his glider to the ground safely. In Holland the landing was much

easier than in Normandy.

�In about an hour and a half our (American) airborne

paratroopers had taken over a small town nearby and had taken 150

prisoners,� Moore says. �I had to stay on the go almost all that night and

spent the next three days on the front lines. A colonel ordered us back to a

drop zone to assist in unloading ammunition at the ammunition dump. At our

last gun emplacement before leaving the combat zone, a German artillery

shell hit in my foxhole, right after I�d gotten out.�

Eleven days after setting the glider down behind enemy

lines in Holland, Moore made it back to his base.

In 1994, Moore and other Market Garden veterans were

invited back for a four-day celebration on the 50th anniversary of Holland�s

liberation. �I got a citation there (in Holland), the Orange Lanyard. They

said it was the highest citation a foreigner could get, although I don�t

know whether that�s true or not.�

His third mission, code-named Varsity, was a flight

across the Rhine River into Germany, on March 24, 1945. By that time, Moore

was stationed in France, about 80 miles south of Paris.

�It was a long haul going into Germany. By then, I

thought, �I�ve been pretty lucky, in Normandy and Holland.� So, I got some

help and an acetylene torch and took an armored seat out of an FW-190 (a

German fighter plane) that we�d captured, and put it into my glider. With

the armored seat, a steel helmet, and a flak vest, I felt pretty good.

�The air force had put down a smoke screen along the east

bank of the Rhine River, so that the engineers could start building a

pontoon bridge. By the time we got there, though, after the three-hour

flight, the smoke screen had moved in 10 miles, right over our landing zone.

When the light flashed on to cut loose from the tow plane, I couldn�t even

see the ground. I wasn�t going to cut loose until I could see something down

there. Anyway, I finally got the glider down � we were heavily loaded, so it

only took a few seconds to set her down after we cut loose from the tow

plane.�

Across the Rhine, Moore carried a communications jeep and

its support personnel. �That�s the way to go � they knew everything that was

happening on the ground!�

Each of his three glider missions was marked by danger

and high adventure getting back to friendly lines and, eventually, to his

bases. Moore recalls the horrific shriek of incoming German 88-millimeter

artillery shells, having to dodge hidden snipers, helping wounded soldiers,

and once, finding a can of peaches from Winchester, Va., in an abandoned

German grocery store.

A Smile, a Handshake and a �Thank You�

|

After the war, Moore married his girlfriend, Roma Saul,

raised a son, R.C. Moore III and a daughter, Margaret. He has five

grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

Moore�s career with General Motors spanned nearly 30

years. He also taught automotive mechanics in Appomattox County and operated

a lawnmower and small-engine repair shop out of his home. He closed the shop

in 1988, when his wife became ill. He lost Roma to cancer in 1989.

While fishing out of his Deltaville cottage in the

mid-90s, Moore rescued a boy in a small sailboat who had been blown far out

into the river by storm winds. As the local newspaper observed at the time,

the World War II veteran was, again, up to heroics, even as a man in his

70s.

Throughout his retirement, Moore has been a willing, if

soft-spoken, representative of his generation and a highly sought spokesman

for the �silent wings� warriors, World War II glider pilots. For years, he

served as Virginia chapter president of the WWII Glider Pilots Association.

At 92, he still leads an active life, dividing his time

between the Appomattox homeplace, speaking engagements, and fishing trips to

his river cottage. When asked what wisdom he would offer, based on a

lifetime rich in experience, Moore repeats advice he got from an older

friend when he returned home after the war.

�When I came back to Appomattox, right after the war, Mr.

R.L. Burke, Sr., president of the Bank of Appomattox, was good to me � he

helped me get this house built. He told me there are three things that will

always do you right in life: a smile, a handshake, and saying �thank you.�

He sure was right � that worked for me then, it�s worked ever since, and it

still works. And it�s the best advice I could offer anyone today.�

|